Statistics from the Chinese Culture Relics Society show that more than 10 million Chinese cultural relics have been lost overseas due to wartime robbery or iniquitous trade since 1840. According to the UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization), about 1.67 million Chinese relics are housed in more than 200 museums in 47 countries. Some estimates put the number of Chinese cultural relics of that kind collected by individuals at 10 times that amount. The figures above reveal the huge amount of China's lost treasures.

The lost cultural relics cover almost all categories, including painting, calligraphy, bronze, porcelain, oracle bone inscriptions and ancient books and records. Most of them are currently owned by museums or private collectors in the UK, France, US and Japan. There are more than 23,000 pieces of Chinese relics in the British Museum. And among the lost 300,000 piece of oracle bone inscriptions, nearly 13,000 are stored in Japan. Limited funding is an obstacle for China to buy them back, according to experts. In recent years, however, the Chinese government has improved efforts to retrieve the precious cultural relics that are kept overseas.

On the occasion of Chinese Cultural Heritage Day, let’s have look at some of the most famous Chinese relics housed abroad.

Gu Kaizhi, Admonitions of the Court Instructress to Palace Ladies, 334-406, hand scroll, ink and colors on silk

|

|

The painting Admonitions of the Court Instructress to Palace Ladiesis housed in the British Museum. |

This painting, dated between the 6th and 8th century - probably an early Tang Dynasty copy - illustrates 12 stories from a political satire about Empress Jia Nanfeng written by Zhang Hua (ca. 232-302). Beginning in the 8th century, many collectors and emperors left seals, poems, and comments on the scroll. The scroll was stored in the emperor's treasure until it was looted by the British army in the Boxer Uprising in 1900. Now it is in the British Museum collection, and is missing the first three scenes. There is another surviving copy of this painting, made during the Song Dynasty that sits in the Palace Museum in Beijing. The Song version is complete in 12 scenes.

Cloisonné jar, Ming Dynasty, Xuande period (AD 1426-35)

|

|

The Cloisonné jar is housed in the British Museum. |

The Chinese perfected the cloisonné enamel technique during the 15th century. By the time this jar was made, it was considered appropriate for imperial use, and many superb pieces were made for palaces and temples. Some of the vessel forms were borrowed from ancient Chinese bronze work. Other shapes, and some of the motifs, resemble contemporary porcelains.

This large cloisonné enamel jar has a dome cover. The body is decorated with a vigorous five-clawed dragon with open mouth, pursuing a pearl among clouds. The lid is also decorated with a similar dragon in clouds, with a finial in the shape of a lotus pod enclosed in petals. The base is surrounded by a band of lappets.

The inscription on the neck of the jar shows that it was made under the auspices of the Yuyongjian, a division of the Imperial Household. The vigorous dragon among clouds parallels the decoration on blue-and-white porcelain of the period. The six-character mark in champlevé enamel is typical of the Xuande style.

The David Vases, Jingdezhen, dated equivalent to 1351

|

|

The David Vases are housed in the British Museum. |

These vases are among the most important examples of blue-and-white porcelain in existence, and are probably the best-known porcelain vases in the world.

They were made for the altar of a Daoist temple and their importance lies in the dated inscriptions on one side of their necks, above the bands of dragons. The long dedication is the earliest known on Chinese blue-and-white wares.

The dedication records that in 1351 a man named Zhang Wenjin from Yushan county presented the two vases and an incense burner to a Daoist temple in Xingyuan (modern day Wuyuan county). Yushan county is in northeast Jiangxi, which lies 120 km to the southeast of Jingdezhen, where the vases were made. This inscription demonstrates that blue-and-white porcelain production was already well-underway at Jingdezhen by 1351. Originally the vases, modeled after bronze pieces, had porcelain rings attached through the elephant head shaped handles.

These vases were owned by Sir Percival David (1892–1964), who built the most important private collection of Chinese ceramics in the world.

Punchbowl with Western trading offices on the Ghuangzhou waterfront, Qing Dynasty, about 1780–1790

|

|

The Punchbowl with Western trading offices on the Ghuangzhou waterfront is housed in the British Museum. |

The exterior of this punchbowl is decorated with a continuous scene of the foreign trading stations built along the banks of the Pearl River in Guangzhou. Outside these warehouses are six national flags, flying from tall posts and identify buildings used by the East India Companies of Holland, England, Sweden, France, Austria and Denmark. Chinese commercial boats are moored along the quay, and Chinese and European merchants, the latter distinguished by their tricorne hats and frock coats, stroll along the dock conducting business. Inside the bowl is a basket of flowers contained within a floral medallion.

From 1715 the Chinese government made Guangzhou the only open port for official trade with Europeans. The factories shown here were built on a strip of land between the city walls and the Pearl River front. Although they had narrow frontage, each building stretched back about 300 meters. They were called “hongs” by Europeans, after the Guangzhou pronunciation of the Chinese word for “company” or “business, hang,” and these bowls are known as ‘hong’ bowls in the West.

As they were not officially allowed into the city of Guangzhou, European traders lived and worked at these rented trading stations during the trading season (roughly June to December). Their ships were disarmed for the duration of their stay and anchored off the island of Whampoa. Small Chinese vessels ferried goods and merchants through the shallower waters to the bund. Chinese interpreters communicated with the merchants, initially in Portuguese, later in ‘pidgin’ English, and – it is thought that - it was not until the late 18th century that any Englishman mastered the Chinese language.

From about 1760 to 1800 the Guangzhou waterfront was repeatedly depicted in oil paintings, watercolors and engravings, so that its changing appearance is well recorded. Architectural details of the warehouses, which were rebuilt in a Western style in 1743 are therefore of interest for dating the views. The appearance or lack of, particular flags, similarly help to pinpoint the dates although some bowls made were decorated with designs from non–contemporary earlier paintings and prints.

The architectural details of the trading stations depicted on this bowl appear in a magnificent eight-meter long scroll in the British Library, painted in China for the Western market between 1760 and 1770 by an anonymous Chinese artist and showing the view from Huangpu district to the city of Guangzhou.

Jade face, late Neolithic period, around 2000 BC

|

|

The Jade face is housed in the British Museum. |

This is a finely carved jade piece with the pattern of a human-like face with large tusk-shaped teeth. The face is finely carved with thread relief indicating distinct features. Its hair is represented by tiny scrolls and lines.

A number of similar faces have been found in China, mainly from Neolithic times. They were a subject of great curiosity throughout early Chinese history: being collected in later periods, and copied, to some degree, by later carvers.

One such face was uncovered in a tomb dated 1300 BC in Jiangxi province, southern China. Another was discovered in a Western Zhou tomb between the 10th and 9th century BC near Xi'an, in Shaanxi province, northern China. We do not know what these ornaments signified to the Neolithic peoples who made them, nor to those who chose to be buried with them in subsequent eras.

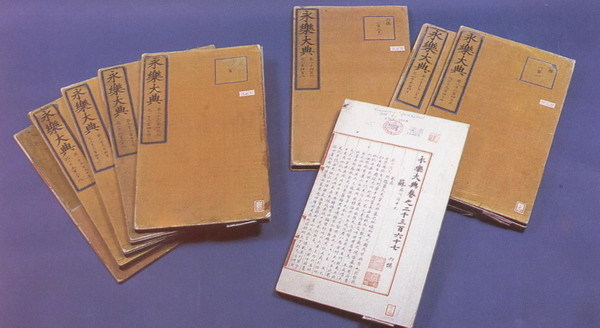

Yongle Canon, Ming Dynasty

|

|

Yongle Canon is separately kept in museums and libraries in Britain, United States, Japan, Korea, China and other countries. |

Originally namedCollection of Classical Literature, theYongle Canonwas compiled in the first year of Emperor Yongle’s reign in the Ming Dynasty (1403), and was finished in 1408.

The Canon contains 22,877 volumes of articles and 60 volumes of table of contents all in 11,095 books, with a total number of about 370 million words. It contains over 8,000 ancient books and records from the pre-Qin Dynasty to the early Ming Dynasty. It’s the largest encyclopedia in ancient China, which was finished over 300 years earlier than the famous Encyclopedia of Britain.

After the encyclopedia was finished, it was preserved in the Wenyuan Pavilion, Nanjing. During the reign of Emperor Jiajing in the Qing Dynasty (1562), a copy was transcribed out of it, when there only became one original and one copy in the world. Unfortunately after that, suffering from wars, fires and pillages by invaders, it became shattered and incomplete. The remnant books collected by public or private collectors all over the world were only about 400 volumes, while the volumes survived in China add to 795, including 730 volumes printed by China Books Publishing House in 1960, and 65 volumes later collected from all over the world.

With great length and extensive content, theYongle Canonis also special with its handwriting. All characters in it were written in regular script by brush pen, supplemented by numerous exquisite illustrations, in which the mountains and rivers are line drawings that are realistic in configuration. The book is hardcover wrapped with gunny cloth, elegant and dignified. It is recognized by experts and scholars at home and abroad as a rare treasure of world history.

The six stone horses of Zhao Mausoleum, Tang Dynasty

|

|

Bas Relief of “Saluzi” or “Autumn Dew” is one of the six stone horses of Zhao Mausoleum, housed in University of Pennsylvania. |

The six stone horse reliefs, known in Chinese as “Zhaoling Liujun” (the six stone horses of Zhao Mausoleum), were commissioned by Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty in 636 and presumably completed in 649, the time of his death. The realistic depiction and exquisite carving techniques of these stone reliefs earn has them a unique place in Chinese art and sculpture history. They bear exceptional historical significance as personal relics of one of the greatest Chinese sovereigns.

They were broken by smugglers in 1914 and two of them were shipped abroad. The stonework is exhibited in the Stele Forest museum in Xi'an and at the museum of the University of Pennsylvania, US separately.

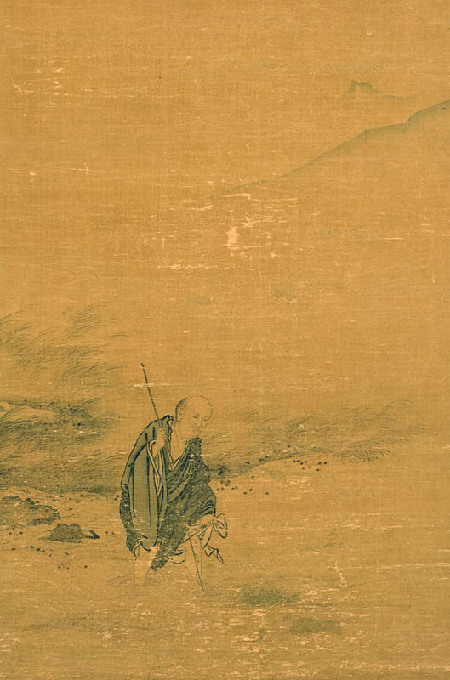

The priest Dongshan wading in the stream, Ma Yuan, Southern Song Dynasty

|

|

Ma Yuan’s paintingThe priest Dongshan wading in the stream, housed in the Tokyo National Museum. |

Ma Yuan was a painter at the Imperial Painting Academy in the middle of the Southern Song Dynasty, and was good at landscape and figure painting. This picture depicts the moment Dongshan Liangjie, the founder of the Caodong Zen, attained great wisdom in a flash when he saw his own shadow while wading across a stream in the middle of his pilgrimage, and is said to be one of few works painted by Ma Yuan himself.